Capital D Disability in Theatre with Julie McNamara at the University of Melbourne

Julie ‘Mack’ McNamara, an Honorary Fellow at VCA Theatre and the Artistic Director of Vital Xposure, one of UK’s leading disability led touring theatre companies. As a Visiting Fellow of the University of Melbourne’s Miegunyah Foundation, she talks to Mireille Stahle about making theatre that puts disability first.

By Mireille Stahle

I have come among you – I am Mireille Stahle. I am 5 foot 6 and slightly over-weight. My doctor says I’m pre-diabetic but I prefer large-and-in-charge. My skin is white. My hair is dyed yellow, the colour of saffron, and the roots are purple. It hasn’t been done in a while and it sits around my face like a skew-whiff halo. I have a big, toothy smile and my eyes are moss-green and gold. I’m dressed in a big red jumper. The jumper is embroidered with an equally toothy smile. I always wear bright colours because I believe they’re aposematic.

I’m speaking with Julie “Mack” McNamara, in Melbourne as a Visiting Fellow of the University of Melbourne’s Miegunyah Foundation. She is an advocate, and something of a reluctant patron saint, of disability representation in theatre, and the Artistic Director of Vital Xposure, a London-based, disability-led touring theatre company.

She is also co-founder of the London Disability Film Festival, and a patron of DadaFest – a leading disability and deaf arts organisation. She’s also white. She stands 5 foot 7, tall and long-limbed. Her legs have walked many, many miles. She’s told she walks like her father, and the girls tell her that her hands are well-hung. She’s a masculine woman, dressed today in a checkered suit. The suit has shoulder-pads because she likes to square up to people in authority.

This is the way that Mack always enters a space. If there are people there with visual impairments and people who are sighted she will still say, “I’ve come among you”. She describes her physicality, how she is perceived in a sighted world, and adds something about her origins, her ethnicity, something about being queer – about being a “fearless butch dyke”.

“I think it’s important to own all of that stuff,” she says. “But also to describe the way I’ve been toldI look, because then when I put it out there, people with visual impairment or blind people come up to me afterwards to say that nobody’s ever told them what they looked like.”

In Mack’s view, when you tell your story, explaining how you’re perceived in the world, and who you feel yourself to be in the eyes of another – you give the opportunity for a person registered blind, or born blind, to trust the voice in the room – to have faith in you. “We often expect too much of visually impaired people,” she says.

Accessibility in Theatre

Mack has come to Melbourne from the UK as a guest of the University of Melbourne, and the Miegunyah Fund Commitee. As a recipient of the 2019 Miegunyah Distinguished Visiting Fellowship, she was charged earlier this month with delivering a lecture on her area of expertise. In addition, she’s come to the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music to run workshops with Dr Alyson Campbell alongside practitioners with disabilities working with Acting, Directing and Dramaturgy students in the VCA Theatre department, to facilitate something radical: making theatre that puts disability first.

“In the UK we spell disability with a capital D”, says McNamara. “We’ve reclaimed Disability because it’s about how we do things our own way”. She describes the “appalling” way that lip service is paid to audience members with a disability, whether it’s through the use of clunky supertitles or interpreters virtually hidden in the wings. “They’ve got somebody at the side, or a bit of text there, stage text …” The “hideous lights” of many productions are a particular kind of hell for people who, like Mack, have an acquired brain injury.

“It is so clunky, so uncomfortable, so awkward,” laments Mack. “Your brain, if you’re deaf, is constantly playing catch-up.” There’s an assumption that the person is the problem because they bring disabilities with them, that something about them doesn’t “work”, but it’s the system that’s failing. That’s why Mack talks about disability-led theatre in terms of “access aesthetics”. Not only does she aim to put extraordinary, marginalised stories centerstage; she strives for an inclusive aesthetic that integrates accessibility into the heart of the work.

Raised by Rebels

Mack cites her mother Shirley, “Queen of the Mersey”, as one of her biggest influences. “If you’re raised by rebels, you have something to fight against, but you also have a particular role model. ‘First, do no harm’, my mother used to always say … She was always an incredible re-inventor of herself”.

Let Me Stay Trailer 2014 from Vital Xposure on Vimeo.

It’s no surprise that Mack describes her play Let Me Stay, a portrait of her mother’s life with Alzheimer’s, as her most important work. Shirley chose the title of the show, inspired by one of her favourite songs. “She was one of the funniest women I have ever met. The sweetest singer – she chose the beginning and the end of the show.” It harks back to the idea of putting disability first: though Mack is the writer, her mother’s input is central.

“I learned to step inside her world,” she says. “It was the most surreal but the most fabulous world and I learned to step in alongside it with comedy and compassion. And let her lead the way. She taught me so much.”

What’s Wrong With Slow?

On one of her early trips to Australia, Mack met one of her long-term collaborators, an actor called Rachel High. Mack describes Rachel as an “Australian National Treasure”, but someone whose learning disability means she’s the often last person thought of in casting rooms in theatre. She is currently doing a degree in Drama and Media Studies at Flinders in Adelaide.

Mack was touring her critically acclaimed show Pig Tales at Gasworks Arts Park in Melbourne in 2006 when Rachel approached her at the bar. “First of all, she said she liked the show,” recalls Mack, “I said, ‘Yeah, yeah, thank you.’ But then she said, ‘You’re coming here to mentor me … I don’t live here. I live in Adelaide. I will talk to my Director and you will come to Adelaide and you will mentor me.’”

And with that Rachel turned on heel, and in no time at all P.J. Rose, director of No Strings Attached Theatre Company, found the funds to take Mack to Adelaide – twice.

Over a period of three or four weeks, Rachel lead the way in a series of workshops – teaching Mack how she uses rhyme and repetition to remember a story. Mack says she put Rachel’s ability first in the workshops.

“She’s had a great impact on the work I do,” Mack says. Society is structured around the old adage that “time is money, time is money, fast, fast, fast, fast, bigger, better, bigger, better, faster, faster … I was getting impatient one day and Rachel looked me straight in the eye and asked, ‘What’s wrong with slow?’.”

That question, she says, hit her like a punch in the gut. “Every message Rachel gets every day of her life is that she’s slow, and she’s too slow” says Mack. And, to my shame, it’s only on hearing this that Rachel’s message hits me too: what’s wrong with slow?

This a fresh approach to theatre. When working with people of all abilities, shapes, and sizes, Mack adjusts the pace to accommodate the slowest person in the room. Why? Because there’s nothing wrong with slow. And there’s also always audio description from the outset:

I’ve come among you. I’ve been trained to be a rhinoceros in the world. I don’t look like a rhinoceros but it’s in my heart, and actually deep inside, I’m a seahorse. I’ve got blonde tousled hair. Some people tell me that it looks and feels like a haystack. I’m Irish. My eyes are blue like the sea but when the dark of night comes they’re just like the Mersey – full of silt.

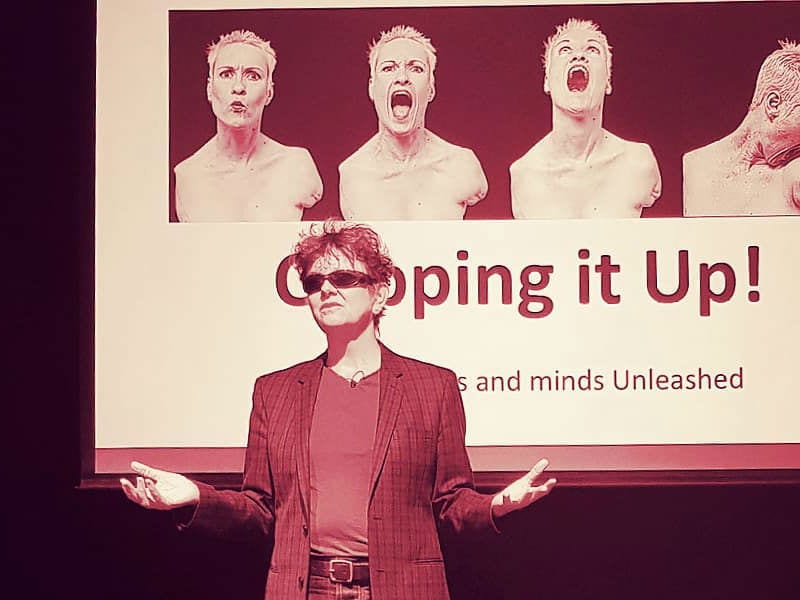

Watch: Miegunyah Lecture 2019: Julie McNamara (Cripping it Up!)

Julie ‘Mack’ McNamara is the Artistic Director of Vital Xposure, one of UK’s leading disability led touring theatre companies within Arts Council England’s national portfolio. She is a Miegunyah Distinguished Visiting Fellow at Victorian College of the Arts, Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, and an Honorary Fellow of the University of Melbourne. Most importantly she is an award-winning artist and an insatiable activist, with a leading voice in Disability Arts.

Rachel High has an extensive acting career and went on to co-create Steak & Chelsea with Julie McNamara in 2008, performing at Adelaide’s Feast Festival directed by Paolo Castro and in London 2009 directed by Caglar Kimyoncu. Under Maude Davey’s direction and the auspice of No Strings Attached (NSA), Rachel performed with Emma J Hawkins in Moira Finucane’s Salon de Dance in the 2010 Feast Festival. Rachel is an active member of NSA and is a founding member of NSA’s Women’s Ensemble, launched in 2015.