Lin Onus: eternal landscape of the artist’s mind

A new exhibition at the University of Melbourne celebrates the work and ongoing influence of the late Yorta Yorta artist Lin Onus.

By Dr David Sequeira, Director Margaret Lawrence Gallery

I kind of hope that history may see me as some sort of bridge between cultures, between technology, and ideas – Lin Onus.

The work of Lin Onus occupies a unique space in the broader context of Australian art. His painted landscapes, which form the core of the current exhibition at the Margaret Lawrence Gallery, display a complex fusion of ideas around place, possession, time and history.

A Yorta Yorta self-taught artist living between cultures and communities, Onus found a way to bring together Indigenous and non-indigenous understandings of landscape and articulate the intersection of two sets of values and points of view.

Onus does not present this intersection as a collision, but rather as a layered coexistence in which picturesque ideals of non-indigenous representations of nature are contextualised within a more ancient and abstract indigenous visual language.

From the mid 1980s, Onus made several trips to Maningrida in Arnhem Land, where he was given stories and designs by community elders. During this period Onus mastered the raark pattern of cross hatching and the “X-ray” style used by a number of bark painters in the region.

Blending this imagery with photo realism, Onus depicted not only the physical attributes of place, but also its spiritual dimensions, allowing him to address political issues while simultaneously generating contemplative experiences connected with creation, continuity and the eternal.

The works in this exhibition were painted in 1995 and 1996 – a particularly fertile period in which the illusory nature of landscape seems to be a central theme for Onus. In these paintings, landscape is less of a place and more of an experience or sensibility.

Onus’ trees, mountains, leaves and sky are presented as reflections, existing elusively on the shimmering surface of the water. His emphasis on reflection and water surface can be understood as a call for deep consideration of one’s experience of life, or more specifically to make connections between oneself and the world.

Onus makes apparent the visible and the invisible qualities of landscape through the juxtaposition of Indigenous and non-indigenous landscape imagery.

Fish, a recurring motif in Onus’ work occupy the domain beneath the surface. Although devoid of flesh, his fish are very much alive – hovering in the water, their curves in tune with its subtle ripples.

In the current selection of work, the stillness of an Australian outback waterhole, the sparkling ponds of Japan and the icy oceans of Antarctica are all claimed by Onus’ fish, a symbol of adaptability, survival and the source from which human life emerged. The fish signal an Indigenous life force – present and thriving regardless of what happens above the surface.

Onus could be considered a visual historian whose landscape paintings reject linear narratives that privilege the notions of discovery and the individual. Unlike Eurocentric understandings of history, there is no suggestion of a conquering hero who forms the focus of the composition.

Onus could be considered a visual historian whose landscape paintings reject linear narratives that privilege the notions of discovery and the individual. Unlike Eurocentric understandings of history, there is no suggestion of a conquering hero who forms the focus of the composition.

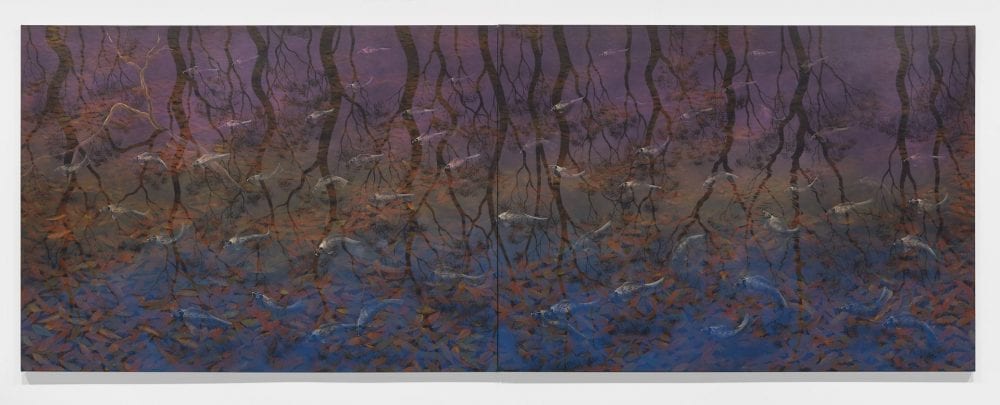

The absence of a single focal point encourages the eye to scan across the canvas – no section of the painting is more or less important. This idea is exemplified in Fish and Leaves (Airport), 1995 (main image, above). Monumentally scaled at over five metres in length, the diptych was originally commissioned for an airport.

With no central figure, Onus depicts a layered microcosm teeming with spiritual presence. The heroes of the work are the gleaming water surfaces, dappled light, leaves and the fish all of which point to an understanding of the land – gently buzzing but potently charged with a quiet energy.

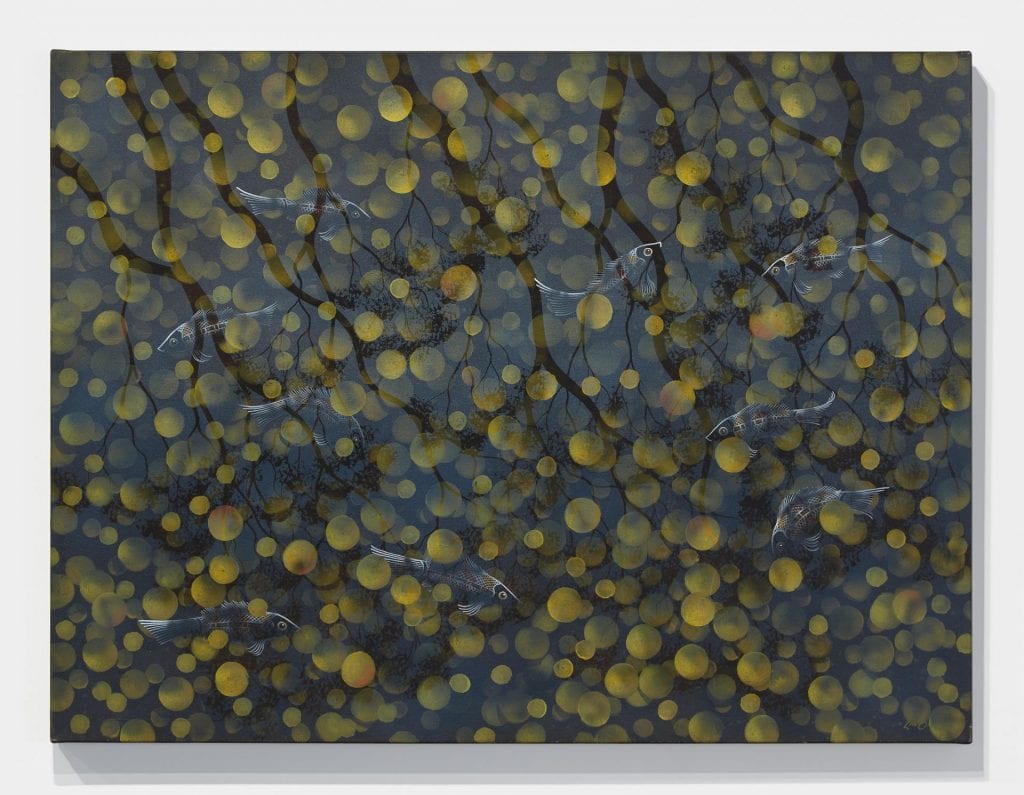

A more mystical understanding of landscape is presented in Fish and Roundweed, 1996. Onus creates an almost abstract setting of yellowy-green orbs for his fish. As in other works, there is no central focal point – the orbs bleed off the edges of the canvas alluding to ideas of endlessness and the cosmos.

This idea is echoed in Dawn at Malwan, 1996. By setting his ghost-like fish in waters that reflect the clouds Onus blurs the distinctions between land, sea and sky – the physical and metaphysical. Stingrays also dream of flying, 1995 continues this theme : “stingrays hover in the sky, displaced from their natural environment but launched into the visionary realm of possibility.”

It seems that for Onus, painting was a way of creating new understandings of time and place. In this light, his landscapes can be understood as addressing the transitory and fluid spaces between tradition and change.

The perennial themes of his work – reflection, coexistence and ownership – have as much if not more relevance now than when Onus painted them more than 20 years ago.

Activist and friend Gary Foley described Onus as: “an artist first and a politician second … he expressed himself through his art, and in doing so created some of the most powerful political statements of his era.”

This is the strength of Onus’ imagery – its capacity to address issues and points of view that are deeply personal yet speak to global concerns.

This article is an edited extract of the catalogue essay by Dr Sequeira for the exhibition Lin Onus: Eternal Landscape, which runs at the Margaret Lawrence Gallery until 11 May. There will be an Exhibition Reception at the Gallery on 11 April (5.30pm–7.30pm). The Margaret Lawrence Gallery acknowledges the generosity of Tiriki and Jo Onus.