Art of war: where conflict meets creativity

The relationship between Australia’s military efforts and sanctioned artists dates back to 1918 but, as the nation’s 63rd official war artist explains, there are as many ways to cover combat as there are artistic sensibilities.

By Professor Jon Cattapan, VCA Director

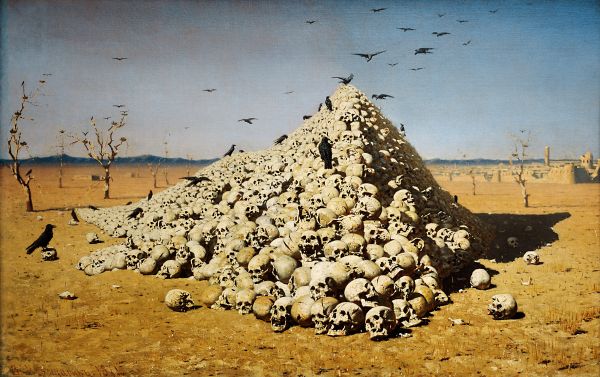

Vasily Vereshchagin’s 1871 painting The Apotheosis of War shows a pyramid of human skulls on a dying landscape, watched over and picked at by birds. Dedicated to “all conquerors, past, present and to come,” the work transcends any one conflict, conveying the horrors of war in a way that text, that photography, never could. Such is the role – or one of the roles – of war art.

Since Vereshchagin’s day, we have grown used to the relationship between war and art, between destruction and creation, but not to the inherent, often surprising power of the art itself. War art documents the highs as well as the lows of the most despairing situations – catastrophes, yes, but also the triumph of the human spirit in times of quite unimaginable duress.

The Victorian College of the Arts and its antecedent institution The National Gallery of Victoria Art School have a long and venerable history with War Artist alumni, and in particular with the Australian Official War Artists Program.

Indeed, while George Lambert is claimed as the first war artist for Australia in 1918, it was the National Gallery School’s alumnus Arthur Streeton who proposed an “official” scheme in 1918, while living in London.

Streeton was appointed as an official war artist in May 1918 and was sent to France, where he was attached to the 2nd Division AIF.

The scheme operated continuously until the conclusion of the Vietnam War in 1975, to where alumnus Ken McFadyen was deployed in 1967. The scheme then went into hiatus until the deployment of alumnus Rick Amor to Timor Leste in late 1999.

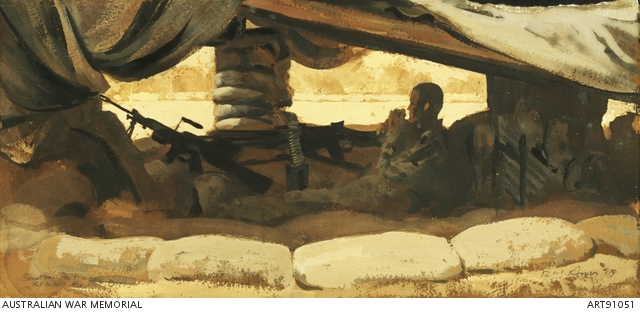

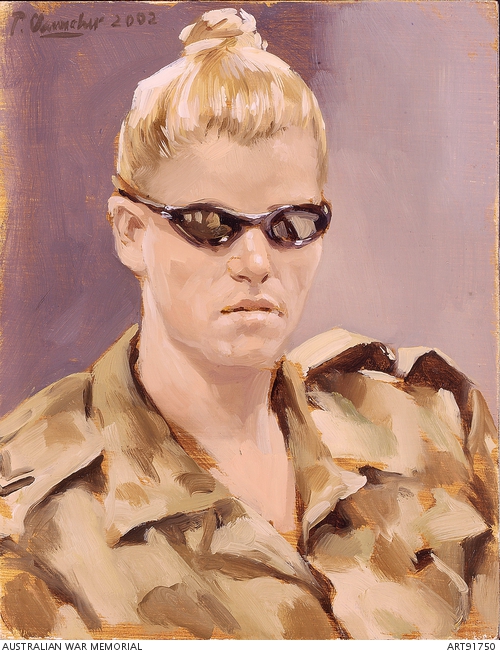

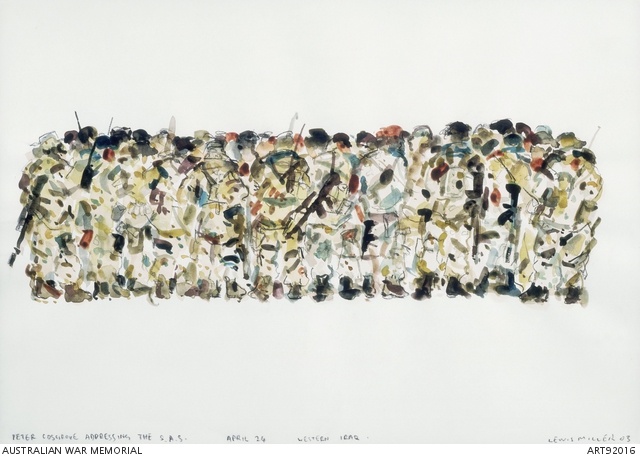

Since Amor’s time, other VCA luminaries have included Peter Churcher (Afghanistan, 2002), Lewis Miller (Afghanistan, 2003), and collaborative duo Charles Green/Lyndell Brown (Iraq and Afghanistan, 2007).

These days the scheme is auspiced by the Australian War Memorial, under the Official War Art Scheme, which commissions artists and collects those works.

Deployment

In my case, the term “war artist” seems, perhaps, a little too dramatic. As Australia’s 63rd official artist, I joined a peace-keeping force in Timor Leste in 2008 and, while there was ever-present security and intelligence-gathering, the country was relatively stable. It was, as they say in the army, “low-tempo”.

In the discussions with the Australian War Memorial representatives that led to me accepting the commission, there was a clear understanding that war artists were not in any way expected to proselytise on behalf of the Australian Defence Forces.

Given invention and imaginative readings are as important to me as any form of social observation, I was curious as to whether one was expected to portray realistic depictions – certainly I was capable of it, but it is not really at the heart of what I explore methodologically.

That concern was quickly dispelled. At one meeting I was reminded that this was, in fact, just a great opportunity to make translocated “Cattapans”.

In other words, I was given license to explore contemporary soldiering through my particular predilections as an artist – a very rich opportunity which ultimately steered my aesthetics and social rationale for years to come.

Best of all, as I had already begun to interrogate ways of picturing surveillance, when I asked for and received access to night-vision technology, I found an extraordinarily simple but effective way to re-cast my work through those deep luminous fields of green and heightened figures captured in night-vision.

Camp Phoenix

In mid-2008, after three days of pre-deployment at the Ennogerra barracks in Brisbane, I arrived at the now decommissioned Camp Phoenix (Timor Leste’s main army base in Dili with two assigned bodyguards and the Canberra filmmaker Rob Nugent).

Timor Leste is a hauntingly beautiful place, and for me it was eerily familiar. The hot and humid landscape feels very much like the north of Australia, only more mountainous – it is, after all, only 600km from Darwin and there is a real sense that it was once a connected land mass.

There was an immediate willingness to make a plan for where I might go and what would be of interest for me to observe. But I soon discovered the famous “hurry up and wait” phrase that soldiers become very familiar with.

In due course, we hitched chopper rides to various forward operating bases: Gleno, Ocussi, Maliana and Vekeki. I lived with the men, enjoyed camp cooking, watched their routines, went along to morning briefings and made a lot of close observational sketches.

While I had visions of kicking back in the evenings to hear soldiering yarns over a beer, contemporary soldiering is such that all my young comrades would retire early to their tents to undertake online learning courses. In any case, Timor Leste was a “dry” mission.

From rugged mountainous terrain to lush tropical forest, the landscape itself had an awesome ever-present visuality throughout the whole journey. But equally important were the Timorese themselves – slight and lightly dressed, with beautiful smiles, they made for a startling contrast to the heavily-kitted and armed Australian soldiers as we made our way through local markets and nearby villages.

I could not help feeling that, for all the friendly engagement and social banter, no-one was entirely comfortable, and that we were conspicuously out of place. We were well-versed in local protocols, particularly when meeting the sukhi (local village chieftains), and yet there was always a certain edge. It seemed to me that all parties were delivering rehearsed and required banter while concurrently searching for an operational clue or two in the sub-texts.

So, how might an official artist for the Australian War Memorial bring together some of these psychologies and local sentiments?

Night vision

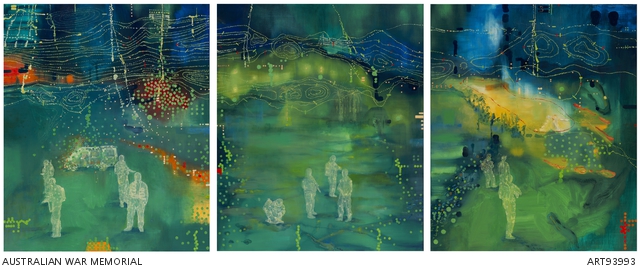

Using an amalgam of local and global environments to test ways of picturing gatherings or mapping territories has been at the heart of my practice. In Timor Leste, that was brought to bear through the lens of the night-vision monocle I was given.

The fact that Timor Leste was a low-tempo deployment meant I could follow the soldiers out on night patrol – a small detail of men, with me protected within their midst, shooting away digitally. Many haphazard shots through a makeshift arrangement utilising the night-vision monocle resulted in a range of rich luminous images.

When I see those images now, I am immediately taken back there – I have that same sense that in those unearthly illuminations there is/was a sense of imminent danger.

Back in my studio in Melbourne, I made a large triptych, Night Patrols, Maliana, which is now held in the AWM Collection (this compendium work conflated many of the patrols and nocturnal places into something of a spectral gathering).

The experience has had a significant influence on my subsequent output. But I especially now feel the creative depth and social worth of that undertaking through an evolving body of collaborative works I have made and will continue to make with my friends and University of Melbourne colleagues, Charles Green and Lyndell Brown.

We have, since 2011, through a successful Australian Research Council Discovery grant, been working in very direct ways as artists to create digital works and paintings together that emanate from our mutual experiences. From this project, we have published a book that illustrates both the experiences and our art: Framing Conflict (MacMillan, 2014).

Our collaborative thinking and practice located around specific wars continues to evolve as a layered and conceptually inclined art that bears testament to continuous global conflict – a sad marker of our times.

In 2016 we were awarded a new grant through the Australian Research Council, to further develop ideas in collaboration and to our “team” has now had the addition of British war artist and RMIT senior academic, Professor Paul Gough.

It was a great privilege to be deployed to Timor Leste as an official war artist and the experience opened up a very rich and meaningful artistic journey for me.

I have become very aware of the travellers before me and since, both the creatives and, of course, more importantly the soldiers themselves. And, like all artists that have experienced theatres of conflict, I feel that there will be a small part of that experience embedded, even if not seen, in my future works.